Return to Theatre Index

Return to Main Page

On October 4, 1996 the Ambassador Theater

in St. Louis was

demolished. It passed with little notice, except by those, like myself, who had wondered at it and tried to save this survivor

of 70 years. I was working for the State Office of Historic Preservation at the

time, but my efforts went against city hall and proved fruitless – see my

article, “The Ambassador Theatre: An Endangered Species”, Missouri Preservation News, Fall, 1977.

My first

experience in the Ambassador was also my first in any movie theater at a time

when many Movie Palaces were beginning to fall to the wrecking ball. I was a

child when I stepped into its palatial “Franco-Spanish Carnival” lobby, but

when I saw the silver-gilt and crystal fantasy set with colorful “jewels” and

dripping with heavy teal-blue velvet drapes I knew that this place, this

experience of going to the movies, was something special, one that I would

never forget.

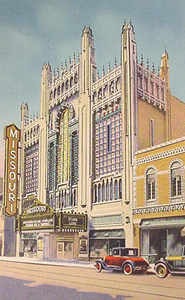

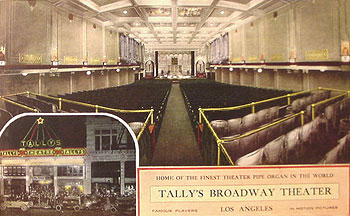

The exterior and

lobby of the Ambassador theatre, St. Louis, MO.

The Theatre images

in this section are taken from postcards and

personal photographs in my collection.

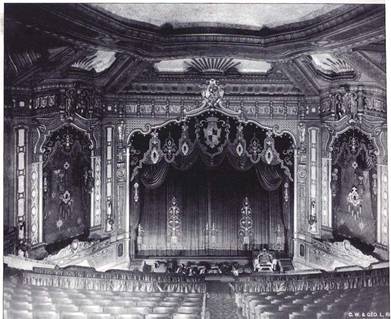

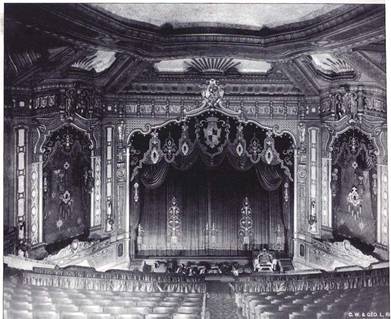

In the auditorium,

Stan Kann at the “Mighty Wurlitzer” organ filled the huge enclosure with the

overture to the first in the series of “Cinerama” movies. As my mother and I

settled into the plush velvet seats, I asked her in a whisper if this was a

castle because there was a coat of arms over the stage. She laughed and said

no, but as the lights dimmed I felt as excited and special as a princess in the

fairyland of that beautiful theater.

In the auditorium of

the Ambassador Theatre

The film began on the curtain and the curtain opened. I

was lost in another dimension - a feeling I can now only compare to the

separation from reality in time and space experienced in this computer age

during a session in cyberspace - a virtual reality where I became part of the

fabulous surroundings and an intimate observer of the story on the screen.

Many writers,

entertainers and architects have noted this hypnotic feeling, this mood - the

projection of the self into another dimension propelled both by the decoration

and fantasy found within a Movie Palace and the

fantasy of the film reaching out into the physical environment of the viewer.

It has been called synesthesia - a sensation

affecting one sense when experienced by another, such as feeling the emotion of

color in a sunset or experiencing musical harmonies embodied in the

architecture of a great architect like Andrea Palladio.

The movie theater itself has been called “The House of Dreams”, a place to

dream in where a patron easily falls under the spell of the “Wizard’s Wand”,

the spell of “illusionland”; “an acre of seats in a

garden of dreams” where the architecture projects the viewer to “patrons’

heaven”, a place to live with the characters on the screen, in another time and

place; a rich self-contained world, excluding all reminders of reality, that

dispels the belief that luxury and fantasy can happen only to other people.

An expressive

name for this physical and psychological environment might be “cinéspace”, the nirvana sought by architects, managers and

showmen to bring the patron back time and again to the Movie Palace. The

crafting of cinéspace began with the earliest store

front theaters and was honed to a fine art from 1913, with the opening of the

Regent Theatre in New York, to

1932, the opening of Radio City Music

Hall and the end of the Movie Palace era. It

continued and was shaped by new developments throughout the Great Depression,

the War Years and the post-war baby-boom era.

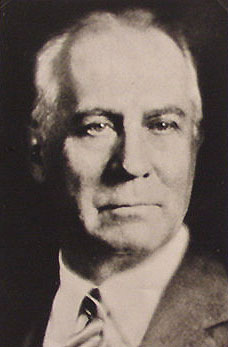

The careers

of two important theatre architects, Carl and Robert Boller,

stretch across this entire period, beginning in 1903 with the design of the LaBelle Opera House in Pittsburg, Kansas passing through

the Movie Palace era with theaters like the Missouri Theatre in St. Joseph

Missouri, the Granada Theatre in Emporia, Kansas and the Midland Theatre in

Kansas City, Missouri, moving through the era of the small neighborhood theater

in the 1940s and into the drive-in craze of the 1950’s. The story of their firm

and their careers is important in the saga of the history and development of

the concept of cinéspace.

Carl (left) and

Robert Boller

But how did this concept develop? How were

architects limited and inspired in the design of these buildings by business

and society during those historic decades? Who were the other famous names

involved with these buildings and what exotic worlds did they seek to create? And after the Movie Palace era passed, what effect did the

decades of the 30s, 40s and 50s have on movie theater design?

Note:

The original version of this article is heavily annotated and can be found, along

with an extensive bibliography on this subject, in my book about the Boller Brothers, Windows to Wonderland, mentioned in

the Bio section. The notes have been removed from this version.

On March 22, 1895 the world changed when Louis and Auguste Lumiére projected the

first motion picture on a screen at 44 Rue de Rennes

in Paris.

The Lumiéres and their Cinématographe

Precursors

to the invention of the Cinématographe, as the Lumiéres called their combination camera and projector, such

as Thomas Edison’s Kinetoscope, had allowed only one

viewer at a time the privilege of watching prize fights, young ladies dancing

or other scenes recorded on intricately spooled film or rapidly flipping cards.

Using Edison’s Kinetoscope

as a guide the Lumiéres developed their small,

lightweight Cinématographe, enabling photographers to

record on film easily for the

first time outside a

specially constructed set building, such as Edison’s Black Maria studio.

In the United States the first projected film was seen

on April 23, 1895 at Koster and Bial’s Music Hall in New York City, projected by “Edison’s Vitascope”

onto a screen of muslin stretched within an ornate gold frame. The show,

advertised as “Edison’s latest marvel”, included short five-minute films of dances, a

prizefight and crashing waves in “Rough Seas at Dover” all to a cheering crowd.

Koster and Bial’s

Music Hall

It is ironic that Edison, the inventor of the

phonograph (1877) and the incandescent bulb (1879), is often cited as the father

of American motion pictures because of his association with the Koster and Bial show. In fact, he at first opposed the projection

of film as a money-losing proposition because he saw no reason to sell one projection

machine when he could sell hundreds of Kinetoscopes

for use by the same crowd. Consequently, he believed that moving pictures would

soon prove to be an economic disaster. Yet the lending of his name to the Vitascope, a projection device invented by C. Francis

Jenkins, a government clerk, and Thomas Armat, an electrician and promoted by Norman Raff and Frank

Gammon for use in music halls, assured

his place in folk lore as the inventor of the motion picture. After the invention of the Vitascope, Raff and Gammon secured Edison’s agreement to develop and

manufacture the device, so forever linking the names of Vitascope

and Edison in the public mind.

By July, 1896 the Lumiéres’ Cinématographe had crossed the Atlantic and was competing

with the Vitascope in the vaudeville program at Keith’s Union Square Theater in New York, and

on October 5 another similar machine,

the Biograph, opened

in a vaudeville program at Hammerstein’s Grand Opera House in that city

with a larger and brighter image that the others. Despite the advances that

made both the Biograph and the Cinématographe

superior machines, the Vitascope eventually won the

commercial contest due to Edison’s business techniques and his exploitation of already

existing distribution channels established for his phonograph.

Films

and vaudeville were linked from the beginning in the development of this new

motion picture technology. But before looking at the many close relationships

between vaudeville and small-time vaudeville houses and later Movie Palaces, it

is instructive to consider the development of vaudeville and other forms of

popular entertainment like itinerant shows, circuses and nickelodeons, that

helped shape the Movie Palace concept.

Vaudeville, the home of variety acts,

comedy and music, probably originated in France as a form of popular urban

entertainment. The 15th century French had called certain songs “songs of the Vau-de-Vire” after a minstrel who lived in the valley (vau) of the Vire in Normandy. In Paris, these were sung on the street

like many other “voix de ville”, or

city songs. By the 18th century they were sung in farces staged by troupes of

actors who struggled against the monopoly of the Comédie-Française and were called

Vau-de Ville, a corruption of the two

terms. By 1852, vaudeville was already established in the U.S. when J.L. Robinson promoted his

tent show as the “oldest established vaudeville company in the U.S.” Such shows featured

ballad singers, minstrel acts, comic songs, gymnastics, jugglers and short

sketches of contemporary life. By the 1880s, in urban areas, this form of

entertainment and its less savory sister, the concert saloon, had upstaged the

minstrel show and

its commentary on vanishing rural plantation life and the “dime museum” display

of freaks of nature and other curiosities.

Between 1896 and 1906 in the countryside

outside of major urban areas circuses and traveling shows went from town to

town, concentrating on communities not included in vaudeville circuits, showing

a few short films over and over as part of their programs. Circuses featured

special structures for the showing of films called “Black Tents “ or “Black

Tops” which were kept totally dark so the spectators could see the dimly

projected films. These films were part of the sideshow entertainment, promoted

to the public by “barkers” haranguing the crowds. But the circuses, essentially

gypsy in nature, never established an urban base due to the intermittent

seasonal nature of their shows.

Itinerant traveling shows included films

interspersed with simple vaudeville and songs in presentations given in town

halls, “opera houses”, churches and local “academies of music”. One

such traveling show company was Cook and Harris High Class Motion Picture

Company based in Cooperstown, N.Y. Cook and Harris traveled throughout New York and New England from 1904 to 1911 with a portable

projector and a selection of films purchased at 12¢ /foot. Bert Cook, a

traveling salesman, and his wife Fanny, whose professional name was Harris to

shield her obstinate family from the shame of a show business connection, did

all the jobs between them. Bert was the manager, projectionist and part-time

singer, and Fanny was the musical director, ticket seller and treasurer. Moving

from town to town with an advance man to drum up business, they offered a two hour

show of 20 to 25 brief films (mostly from French film companies) interspersed

with songs by Bert and piano solos by Fanny. Soon audiences began demanding

different and better films, so Cook and Harris began renting from film

exchanges that developed to rent films rather than sell them.

But the end for traveling itinerant shows and

smaller circuses came with the rise of “store shows” housed in permanent

buildings that changed their programs semi-weekly or even daily. As film became

more popular and profitable, enterprising businessmen rearranged the facades of

their storefronts, knocking out a section here and there to make small entry

lobbies for these new theaters.

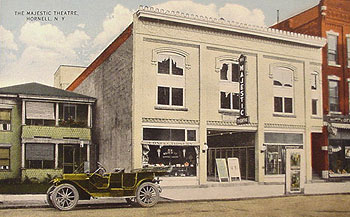

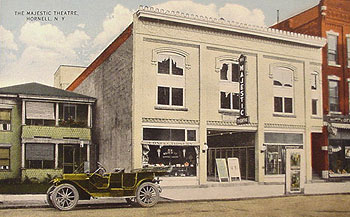

A store show in Hornell, N.Y.

A store show called the

Princess Theatre, location unknown

They

often cleared merchandise from a section of the lower floor, usually at the

rear, hung a curtain and showed films. As the popularity of films grew,

businesses became devoted only to films, clearing other merchandise out

entirely, bringing in chairs and adding a box in the entry way from which to

sell tickets (the box-office). The

“store show” or theatrelet was born and flourished

from 1902-1917.

When John P. Harris and Harry Davis

opened a store show in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, in 1905, a flash of

entrepreneurial genius ensured that they and their theater would provide a firm

economic base for the growth of the movie industry and the development of the

motion picture theater, and that they would become famous in the bargain. They

called their theater The Nickelodeon,

“nickel” for the price of admission of 5¢ and “odeon”

from the Greek word for a covered theater. The term caught on like wildfire and

became a generic term for store shows after this date.

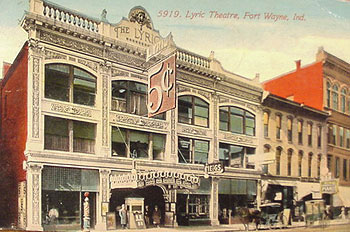

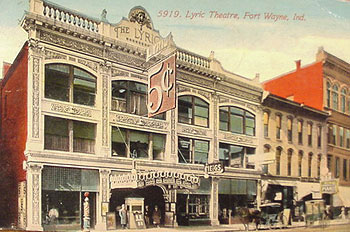

A Fancy Nickelodeon

in Fort Wayne, Indiana

To make

more money, Harris and Davis also adopted a policy of continuous showings from 8:00 AM to 12:00 midnight, like the vaudeville houses of

F.F. Proctor who advertised with the slogan, “After breakfast go to Proctor’s,

after Proctor’s go to bed”. Even at that, all of the Nickelodeon’s 96 seats

were constantly full. This

was the beginning of “the nickel madness” viewed by critics of the day either

as good, get-thrills-quick fun for the diverse populations of urban areas, or as an agent for disaster for urban youth

due to the darkened theater interiors, lack of adult supervision and an

audience believed to include kidnappers, pickpockets and thieves. By

1900 estimates are that 8000 nickelodeons nationwide took in over $91,000,000

annually. In New York City alone 1.2-1.6 million people were

estimated to attend nickelodeons at least once a week and .many went far more

often, some practicing “nickelodeon hopping” as a pastime.

Though some were located in previously

established legitimate theatres, a typical nick was a tiny, long and narrow

undecorated room with 199 seats or less to avoid theater license fees of $500

or more for places of amusement with over 200 seats. The walls were plain and

aside from a few potted palms sometimes found near the screen, decoration was

not used since the theater had to be totally dark to see the dimly projected

films that ran continuously. Seating was

on ordinary kitchen chairs in front of a screen of cloth stretched across a

form. Four films, 5 to 15 minutes each

in length, usually constituted a show, so the entire program was repeated as

many as 20 times in a day. Shows changed

every few days or, in larger urban areas, every day. Comfort and safety were

hardly considered until the passage of ordinances to regulate such things

beginning in 1909.

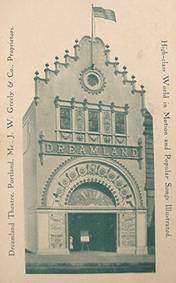

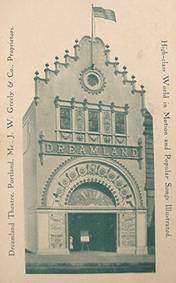

Nicks typically had exotic names like

Dreamland, Aladdin, Paradise or names emphasizing the novelty of this new form of entertainment -

Electric, Cameraphone, Novelty.

The Dreamland Theatre

in Portland, Maine

In 1910 a

film manufacturing company in Chicago even sponsored a contest to

rename the generic name for these store shows. To replace “nickelodeon”, names were proposed

like Photoplay, Photo Drama, Kinorama or Photodrome, but most exhibitors chose to stay with the

established name “Theater” or “Theatre” to designate their businesses.

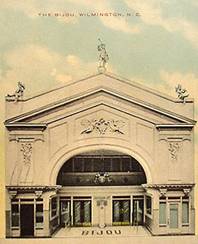

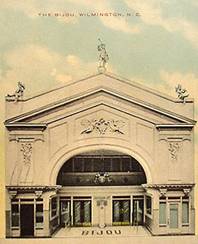

The front of a nick was considered the

center of its advertising and so was seen as the most important decorative

feature of the building. The recessed

vestibule of the store front was dressed up and usually capped with an arch to

draw patrons in visually and spatially as they passed in the street.

A typical Nick

entrance

Whole

facades, cupids, caryatids and all, could be purchased

from supply catalogues to make the front of any nick stand out on a street full

of other businesses. Light

bulbs were used by the hundreds outlining decorative motives and the names of

the nicks spelled out in large letters, usually in pressed tin. This

decoration, combined with advertising posters, the box office and often a

barker on the sidewalk in front accompanied by performers like pianists visible

through special windows in the façade, led to vivid descriptions of these

buildings as “High Coney Island” or “the apotheosis of pressed tin and the

light bulb.”

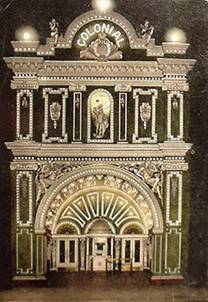

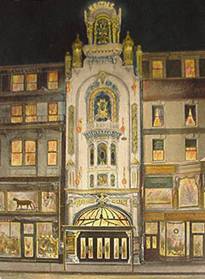

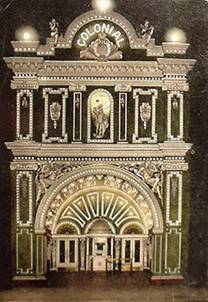

(Left) The Butterfly

Theatre, Milwaukee, Wisconsin and

(Right) the Colonial Theatre, Wichita, Kansas

Along with the nickelodeon, the large urban

vaudeville and the often simpler “small time” vaudeville theater exerted the

most influence on the development of the Movie Palace. On one hand, large ornate houses

like those associated with the B.F. Keith vaudeville circuit in the eastern U.S. featured short films as part of

their programs. And on the other, a second generation of movie theaters called

“small time vaudeville” theaters because they included with their major film

attractions a few small vaudeville acts, grew up replacing the aging nickelodeons.

B.F. Keith, a showman who began as the

proprietor of “dime museums” and concert saloons in Boston in the 1880s, became successful

with his string of large ornate vaudeville houses that emphasized luxury,

comfort and the happiness of the patron and his family. Typically, a Keith

theater featured a large recessed entryway flanked by Classical columns and a

prominent sign featuring his name. The upper facade was often enhanced with

further Classical features, capped with arches and further embellished with

bright electric signs, as is seen in the case of Keith’s Memorial Theater in

Boston. The lobby of a Keith was always noted for its luxurious appointments,

gilded ticket booths, crystal chandeliers, lavish use of marble and murals

depicting the Performing Arts, as well as large panels filled with advertising

for current and upcoming shows.

Keith’s New Theatre,

Boston, Mass.

Keith’s

New Theater in Boston, opened in 1894 to 2000 invited guests, among them the Vanderbilts, Astors and other

cream of New York society, and rave reviews claiming that “the age of luxury

seem to have reached its ultima Thule.” The combination of Romanesque

and Louis XV decoration found in its auditorium done in pale green and

rose enhanced by brocades, gilding,

murals depicting Dance, Music and Comedy by the Italian artist Tojetti, and a heavily gilded proscenium arch made it stand out as the first in the line of

elegant vaudeville houses to come.

Keith’s Proscenium

in Boston

In smaller cities and towns, and in large

cities where they competed with vaudeville, a second generation of movie

theaters grew up after 1910 devoted mainly to films, like the nicks, but with

slightly higher admission of 10¢ - 50¢ for reserved seats. The attraction was

not only the ornate facade designed to draw customers to these new or converted

store fronts, vaudeville or legitimate theaters, but also the added interior

decoration and the addition of lesser known vaudeville acts in a secondary role

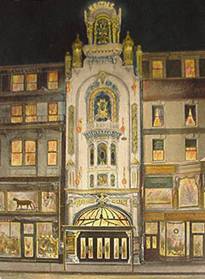

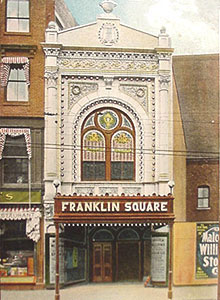

to the film. The facades of these small-time vaudeville theaters usually

featured the newest most popular decorative material of the day - terracotta.

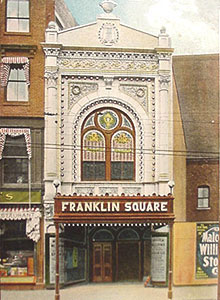

The terracotta

fronts of the Franklin Square Theatre, Worcester, Mass.

and the Liberty Theatre, Los Angeles

Due to the

increase in use of this material during this period largely on the facades of

theaters and other commercial buildings, the terracotta industry in the U.S.

advanced after 1910, producing a material that was durable and inexpensive which could be colored and molded

to fit any decorative plan. Small-time vaudeville theaters also differed from

nicks in that they offered improved safety conditions, elegant surroundings,

even uniformed attendants for only a slightly higher admission, so they greatly

improved the image of movie-going up to World War I. With increased

seating capacity and patronage and higher ticket prices, this form of

entertainment effectively ended the store show business while producing a

generation of motion picture theater entrepreneurs and owners like Marcus Loew and William Fox whose names are still synonymous with

entertainment today.

As small-time vaudeville developed, the

adoption of municipal codes regarding theater construction, the introduction of

longer feature-length films like Intolerance

(1916) (D.W. Griffith) developed in competition with European imports, and the desire of theater owners anxious to

upgrade their image and attract family business led to the development of the

“motion picture theater”. At this period, this kind of theater was a one story

box, sometimes called a “decorated shed”, which was adorned on the interior to

enhance the movie experience during prologues and intermissions of shows which

were now too long to be shown continuously.

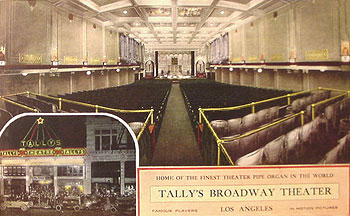

One of the first such theaters was Tally’s Broadway Theater opened in Los Angeles in 1910.

In the years just before World War I, all these strands of

entertainment architecture were woven together to give birth to the

full-fledged Movie Palace : typically an

urban theater constructed for first-run movies, with 1000-5000 seats including

a balcony or two and a mezzanine, lavish decoration recalling past

architectural styles, a liveried staff of ushers and doormen, a first class

orchestra and a large pipe organ for matinees when no orchestra was present and

a complete stage and fly setup for presentation of live shows to enhance the

silent movies. The first building generally acknowledged to fit this

description was the Regent (1913), followed closely by the Strand (1914), both in New York City, though others like the Columbia

Theatre in Detroit (1911) claim the fame as well.

Two interior views of the Strand Theatre in New York City

Important features of a Movie Palace include an ornate ticket booth, or

box-office, in a prominent position near the sidewalk to attract impulse business . Above the box-office, the brightly lit projecting

marquee served as an advertisement and also as a shelter in bad weather to

encourage the patron to wait in line regardless of rain or snow. The decoration

and posters advertising upcoming films in the recess below the marquee and the

large windows in the doors and walls of this area gave a view of the luxurious

lobby, and also served to suggest to the patron that she was already inside the

theater before she purchased her ticket.

Just inside the theater door, the lobby

of the Movie Palace served as a prelude to the lavish

foyer and auditorium. A large commodious

space was needed for the crowds awaiting admission to the auditorium, but

elegance was key here to excite patrons with the

spirit of romance and make them forget they were waiting. One of the

most frequently used decorative features in lobbies was the Grand Staircase,

inspired by, if not copied directly from, that found in Garnier’s

Paris Opera.

The stair of the Paris Opera (left) and

that of the Paramount Theatre

in New York City (right)

Fine

paintings exhibited on stands as well as on the walls, statuary, rugs,

tapestries and fine, often antique, furniture was often exhibited here within

surroundings of crystal, gilding and marble.

The lavish decoration continued into the

auditorium where the proscenium arch, the most prominent decorative element of

that space, drew the most attention. This feature was first seen in small ducal

theaters like that of the Farnese family in Parma,

Italy (1617) though ancestors of it had can be found in buildings

like Andrea Palladio’s Teatro

Olimpico in Vicenza (1561),

which itself was inspired by the writings of Vitruvius,

the ancient Roman architect, and the scaenae frontes of Roman theaters like that found in Orange,

France which dates to the Augustan period.

Scaenae frontes

of the Teatro Olimpico

at Vicenza, Italy(left) and the

Roman theatre at Orange, France (right)

According

to Simon Tidworth:

“The spread of Italian methods of staging

meant that the theatre was increasingly seen as a place of illusion, of make

believe. The illusion depended on scenery; scenery made a picture; the picture

required a frame. Hence the proscenium arch”.

The buildings cited above show that the

arch motif served even from ancient times as both a backdrop for action on a

stage and as a frame for it. In the Movie Palace, the proscenium was emphasized

and embellished. In addition, it was set off by ornate design features called

organ screens on the adjacent side walls which replaced the Opera Boxes of

legitimate theaters and served to mask the chambers where the organs were often

located. Later, as the use of

larger organs located in the orchestra pit became more common, the organ

screens served only as decorative flanks to the ornate proscenium and as

projections of it into the auditorium.

This lavish decoration of the Movie Palace, though seen by critics and

architects of the day as honestly expressing the purpose of a building designed

for fantasy and entertainment, hid beneath it the new and rapidly developing

technology of movie theater design, soon to be considered a specialty in the

field of architecture. In the early years of the movie theater, one

consideration of design and construction was acknowledged to override all

others no matter what the theater type - the importance of sight lines and the

placement of the projection booth in relation to the screen to prevent

distortion of the screen image and the onset of the “keystone effect” where the

image was wider at the bottom than at the top.

As store front and legitimate theaters converted to moving picture

theaters, it was soon recognized that it was not enough to simply add a projection

booth to the rear or in the balcony as some advocated. Existing balconies and

mezzanines in older theaters presented obstacles to projecting the film at its

ideal angle of 12° and ideal “throw distance” of 60-85 feet from the screen, so

bigger theaters designed just for movies resulted. With sight lines established

so that all patrons could have an unobstructed view of the screen to an area

above the proscenium arch, the next important consideration was the design of

the projection booth. A typical booth was located to the rear of the balcony or

just under it toward the front and was designed for safety first due to the

flammable nature of the nitrate film then in common use. This fact alone made

this the most dangerous place in the theater.

Consequently, this room was carefully constructed to be fireproof with

an escape route for the projectionist and shutters over all openings that

closed automatically in the case of fire to prevent smoke from escaping and

causing a panic. Fires such as the devastating accident at the Iroquois Theater

in Chicago had happened often enough to

cause concern and bad publicity. After 1909 and the general institution of

stiff regulations regarding theater construction, ample ventilation was

required in this room as was a firm foundation to prevent noise and movement in

the theater caused by the projection machines.

After consideration of sight lines and

the location and form of the projection booth, the regulation of the continuous

flow of customers circulating in and out of the auditorium at the same time was

a major concern. Exits and entrances had

to be provided which met city codes and provided separate pathways for those

entering for one show and those leaving from another. Steps had to be avoided

completely in the auditorium and wherever possible in the rest of the theater,

especially in areas darkened during the show, so sloping floors and ramps

heading to and from the balconies and the mezzanine became common.

Other important practical considerations

in a Movie Palace included the screen type (mirror,

flat white plaster, aluminum based powdered plaster) and its frame which was

usually of black, blue or grey velvet to help the 15’ X 20’ image stand out in

the large theater interior.

Electrical installations for the stage,

projection booth and especially for the lighting were the final key in motion

picture theater building technology. Lighting was important for safety (aisle

lights) and to emphasize the decorative architectural elements (cove and

recessed lights, chandeliers, fixtures) to project a soothing mood of illusion

within the auditorium. Special forms of lighting were used to

enhance individual presentations, such as that provided by the Brenograph machine described below. Lighting was so

important that color schemes and decorative elements could not be finalized

until the lighting engineer, designers, architects and decorators agreed on a

unified approach.

The marriage of film art, decorative art

and technology that produced the movie palace had one principal purpose - it

was “the grandeur that spelled M*O*N*E*Y”.

But along the way to riches, designers and architects took great pains

to enhance their portals to cinéspace to bring

patrons back again and again.

The aim of theater designers, managers

and impresarios was “to out Baghdad Baghdad” by

creating architectural fantasies full of “exotic ornament and colors to give an

atmosphere where the mind is free to frolic and become receptive to

entertainment.” Designers wanted to be on the cutting edge of popular

architecture, but they also sought to express the purpose of the theater

through the architecture. Rich extravagant adornment was considered necessary

to express the entertainment and fantasy of going to the movies and to make the

patrons feel like millionaires, forget their daily urban industrial existence

and relax in a land of romance. The architect Charles Lee, who designed his

theaters guided by the

credo that “the show starts on the sidewalk” , explained that the

customer came to the movies seeking another world. The architect, he believed,

should provide this with decoration that would bring on a mood of entertainment

in which the customer could abandon all cares and enter “Patrons’ Heaven”,

another term for cinéspace. To be in a Movie Palace was to be somewhere, to be excited by glamour, to be titillated. One

beautiful vista after another from facade to lobby to foyer to auditorium

offered a chance to live like a King for 15¢.

Harold Rambusch

of Rambusch Decorating Company, a firm that worked

closely with many famous Movie Palace architects including the Boller Brothers , discussed his

decorative philosophy in 1930 and his thought speaks for the age in which he

lived. He believed in catering to the mind of the patron through her eyes to

affect her comfort and mood; to allow the customer to imagine herself as a

wealthy person in luxurious surroundings. Seats should be especially comfortable, colors should be warm and golden to appeal to

the psyche. Gilding should be used for richness because even a little gold will

reflect when the house lights are dim to add to the atmosphere of richness.

To illustrate these concepts, the

architecture can speak volumes. Architects like Thomas Lamb, John Eberson, Cornelius Ward Rapp and George Rapp and the Carl

and Robert Boller and impresarios like Sam Rothafel provided many elegant and exotic caverns of cinéspace.

Thomas White Lamb, a Scottish born

architect, was a member of the American Institute of Architects by 1892 and was

designing theaters as early as 1909. Lamb designed the first theaters built

solely for movies, the Regent and the

Strand both in New York City, and worked closely with William Fox and Marcus Loew throughout his career designing theaters like the

Capitol in New York in a style he drew from early American architecture and the

eighteenth century designs of the Scotsman, Robert Adam.

Two interior views

of the Rivoli in New York City by Thomas Lamb

Classical

details, gilding and “Grecian” friezes in white on pale blue reminiscent of the

pottery of Josiah Wedgwood were his trademarks at this period. His approach,

which has come to be called the “Standard” or “Hard Top” school of theater

design, is seen as a natural development from opera house and vaudeville

theater design of the nineteenth century with the added technological features

demanded by the movies. By the late 1920s Lamb, sensing a demand for something

more “flashy”, changed his philosophy and began designing more opulent and

often exotic theaters like Loew’s 72nd Street Theater

in New York with a lobby of exotic columns and scalloped arches inspired by the

courtyard of the 14th century Adinah Mosque

constructed as a tribute to the artisans of Maldah,

India. Lamb chose this motif as a tribute to this style of building, which he

felt was an example of workmanship that was purely American. It was

in his own words “like a temple of gold set with

jewels...pageantry in its most elaborate form...it casts a spell of mysterious

adventure to the Occidental mind, of the exceptional...”

John Eberson,

a contemporary of Lamb’s and a collaborator of his on some theater projects,

was born in Austria and began his architectural career in St. Louis, Missouri

in 1908 designing small town “opera houses” , gaining the nickname “Opera House

John”. In 1922 he designed the first theater in the second major school of Movie Palace design, the “atmospheric”

or “Stars and Clouds” school, an idea he originated which became synonymous

with his name. In his own words (speaking of himself in the third person) he:

“visualized a magnificent

amphitheater set in an Italian garden; in a Persian court; in a Spanish patio,

any one of them canopied by a soft moonlit sky. He borrowed from Classic,

ancient and definitely established architecture the shape, form and order of

house, garden and loggias with which to convert the theater auditorium into

Nature’s setting. It became necessary to study with utmost care the art of

reproducing ancient buildings in form, texture and colors; it was more

important to intelligently, appreciatively and artfully use paint, brush and

electric light, tree ornament, furnishings, lights and shadows to produce a

true atmosphere of the outdoors without cheapening the attempted illusion by

overdone trickery...It offered an atmosphere of intimacy,-a highly desirable

feature in theaters...”

In an atmospheric theater the ceiling is

painted blue, left bare and surrounded on all sides by lush architecture drawn

from European prototypes suggesting exotic themes.

The atmospheric

interiors of the Tampa Theatre in Tampa, Florida (left)

and the Majestic

Theatre in San Antonio, Texas (right)

According

to Eberson “we create the deep azure blue of the

Mediterranean sky with a therapeutic value, soothing the nerves and calming

perturbing thoughts”. It is only when the lights are dimmed that an Atmospheric

comes alive with stars, clouds and other effects projected across the blue

“sky” by machines like the Brenograph. This machine

was a combination spotlight, slide projector and moving effects projector that

could tilt and swivel to cover any part of the theater ceiling with stars,

clouds, angels, rainbows, birds and other effects. In addition, it may have

been used to create decorative effects on the area surrounding the movie screen

to enhance the story line - hearts and flowers for love scenes, rain or snow,

etc. Up to four Brenographs were used simultaneously,

projected from concealed compartments within the side walls of the auditorium , to enhance these architectural fairylands.

The most famous Eberson Movie Palace was the Paradise Theater in Chicago (1928) designed for the Balaban and Katz chain. It was an eclectic dream of

European-inspired detailing featuring Zodiac and mythological themes in its five story lobby that echoed the stars and clouds

produced in the auditorium. The demolition of this beauty in 1957-58 was a

tragedy in the history of American architecture. But this theatre had its

revenge. The difficulty of the job due to walls with a thickness of 3’ and more

drove the demolition contractor first to bankruptcy and then to suicide.

The theaters of C.W. and George Rapp for

the Publix-Paramount chain and Balaban

and Katz were of the Hard Top variety and aimed for eye-bugging opulence, a

“celestial city - a cavern of many- colored jewels where iridescent lights and

luxurious fittings heighten the expectation of pleasure. It was richness

unabashed...” Influenced by a tour of France early in their career, the Rapp

brothers were known for their adaptation of European, and particularly French,

royal architecture, such as the St. Louis Theater in St. Louis, Missouri where the lobby is an adaptation

of the chapel at Fontainbleau Chateau (16-17th c.).

The St. Louis

Theatre (Powell Hall) (left) and

the chapel at Fontainbleu

(right)

They were

also fond of borrowing the stairs of Charles Garnier’s

Paris Opera as they did for their Paramount Theater in New York City. The Royal Chapel of Louis XIV at

Versailles (1689-1710) was adapted by the Rapps in the $2,000,000, 4500 seat Tivoli in Chicago, a theater considered so perfect,

so overwhelmingly French yet intimate, that it became a role model for many

architects and designers.

In addition to the opulent styles of

Rapp and Rapp’s Baroque and Eberson’s Italian

gardens, the Art Deco style was popular in movie theater design and decoration

in the 1920 and into the 30s. This style was characterized by applied

decoration featuring sunbursts, crescents, geometric forms, dripping fountains,

tropical leaves and flowers, brilliant colors, skyscraper/pyramid designs,

luscious materials and textures coupled with exotic motives and decorative

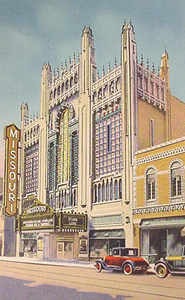

themes like Egyptian, Mayan, American Indian, Persian or Chinese. Fine examples of this style are the

façades of the Missouri Theatre in St. Joseph, and the Watseka Theatre in

Watseka. Il., and the interiors of Grauman’s

Egyptian in Los Angeles and the Missouri Theatre in St. Joseph.

The Watseka Theatre, Watseka, IL. and the

Missouri Theatre, St. Joseph, MO.

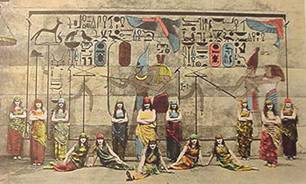

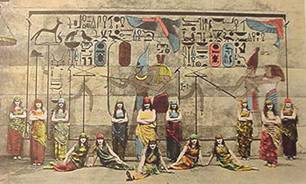

Two interiors of Grauman’s Egyptian with usherettes

dressed a Egyptians maidens

An interior of the

Missouri Theatre in St. Joseph, inspired

by the tent of the

Persian King Darius.

Art Deco

was born at the Paris Exposition Internationale des arts decoratifs et industriels

modernes held in 1925, and it thrived in the

later 20s and into the 30s in Europe and America as an expression of

modernity. The Great Depression called a

halt to the use of expensive materials required for this luxurious look, but

simpler manifestations of this style seen especially on the facades and in the

auditoria of smaller neighborhood theaters continued to be designed even

through the Depression and beyond.

One of those most responsible for the success of the Movie Palace idea was not an architect but a

showman. Sam Rothafel, known as Roxy,

was an impresario who designed his theaters to please the public with special

care for architectural surroundings.

Sam Rothafel (Rothapfel)

From small beginnings running a nickelodeon in Pennsylvania, Roxy

helped shape New York and Broadway in the first two

decades of the 20th century and was responsible for the success of many

theaters including the Regent and the Strand discussed above.

But he is remembered most for his own theater, the $8,000,000 Roxy, the “Cathedral of the Motion Picture”, which opened

in March, 1927.

The Roxy exterior and Rotunda

The Roxy was decorated by the

firm of Harold Rambusch and was famous for its size

(6200 seats) and its opulent eclectic decoration with Renaissance details

grafted onto Gothic forms with Moorish overtones reminiscent of the “plateresque” school of Spanish silversmithing.

Its five story Rotunda, large enough to hold 2500

waiting patrons, was embellished with heavy gilded detailing and columns of verde antico

marble.

But the Roxy’s real claims to fame were its staff and its mode of

operation as a true luxury palace catering to its patrons’ every whim. The Roxy had a

staff of hundreds - ushers, page boys, footmen, doormen, elevator operators,

cashiers, nurses (in its small hospital) and matrons who babysat and acted as

beauticians and seamstresses all held together

with spit-and-polish military precision and strict drilling by an

ex-Marine Drill Sergeant and a Morale Officer. In addition, the Roxy Symphony Orchestra of 110, the 100 voice Roxy Chorus and countless performers, stage personnel,

carpenters, painters, etc. filled out the staff. The ushers were especially

highly regarded, and were immortalized forever in the Cole Porter song “You’re

the Top”:

“You’re the top,

you’re steppes of Russia,

You’re the pants on a Roxy usher.”

All this

grew from Roxy’s philosophy that success in any

organization arose from pride in the institution and an esprit de corps. Success achieved would then translate itself into

an atmosphere where the patron would feel she was a special guest in a special

place, a place that was “hers”, a place of courtesy and service. Within these elegant surroundings and catered

to by a trained staff, a patron could enjoy a typical Roxy

stage show of 25 minutes. Such a show might include an overture of music by

Puccini, a fanciful ballet with newcomers like Martha Graham, a newsreel, a

short film, a precision dance by the 16 Roxyettes

(later the Radio City Rockettes), an operatic

selection, a choral selection by the Roxy Chorus, a

finale, an organ interlude played on three giant Kimball console organs and the

feature film.

All the opulence created by these

architects and by impresarios like Roxy was a means

to an end. To quote Marcus Loew, “We sell tickets to

theaters not movies” and John Eberson,

“Prepare Practical Plans for Pretty Playhouses-Please Patrons-Pay Profits”.

Overwhelmingly, writers of the day report that the reason for the embellished

Movie Palace was to attract paying patrons, to make them feel happy and

important, to help them forget their day to day cares and get lost in the

luxurious surroundings of the movies in the hopes that they would feel there

was so much to see that they would have to come back again and again. The

theater was seen as a “show window” to lure business. Marcus Loew, founder of the Loew’s

chain, was quoted as saying “The gorgeous theater is a luxury and it is easy to

become accustomed to luxury and hard to give it up once you have tasted it.” Manuals on theater management covered

many pages with instructions to owners and managers on ways to lure in an

audience already seeking and receptive to luxury and romance.

But the business of the movies had to

rely on more than just the elegance factor to draw crowds. Beginning in the

first decade of the twentieth century with their acquisition of vaudeville

theaters and into the 1920s and early 1930s, the height of the Movie Palace

mania, the “Big 5” (Loew’s, Fox, Warners,

Paramount and Metro Goldwyn Mayer) absorbed theaters in cities and towns all

over the U.S. to establish their own private distribution systems and insure

profits for their films, often by nefarious means and sometimes terror and

extortion. Studios used ‘wrecking crews’ to travel to small towns and threaten

theater owners with midnight demolition unless they joined up

with their studio system. By the 1930s

more than 500 feature films were produced each year and released directly to

neighborhood studio owned theaters, insuring huge profits. The film industry had become a “Big Business”

by adopting the mass production-mass distribution strategy of the chain store

that had developed at about the same time. Production companies released an

increasingly standardized product directly to hundreds of studio owned theaters

on a national level at a decreasing cost per unit. For this reason, it became

important that each link in the “chain” attract the most patrons possible -

hence the de luxe

comfort of the Movie Palace. Research suggests that managers

were encouraged to keep their theater’s public image conservative and refined

through rigid training of their staff (like that practiced by Roxy) and to keep costs down by hiring predominantly young

females who would work for less.

Only the arrival of air conditioning in

the late 1920s had more of a

positive effect on movie attendance than did increasing the

elaborate exotic decoration of Movie Palaces. And far from being economic white elephants, as claimed by some,

Movie Palaces were designed and built to generate more than enough

revenue to cover costs and were highly profitable.

In what ways did moving picture

theaters, vaudeville theaters and the later Movie Palaces interact with and

help shape American society in the early 20th century? Contrary to popular

belief that early movie audiences in nickelodeons and vaudeville theaters were

made up largely of poor and immigrant members of society, studies of population

distribution in relation to the locations of movie theaters in New York has

revealed that audiences were made up primarily of working class and middle

class people who desired to experience the rich life they were striving for or

were beginning to become accustomed to.

Moreover, recent studies have suggested

that women played a large role in the popularization and acceptance of the

movies and movie theaters. To gain the business of women who were increasingly

on the street for legitimate reasons like shopping or work, proprietors of

places of entertainment like “concert saloons”, male bastions called the

“portico to a brothel”, began to change their establishments to the

more acceptable nickelodeon or vaudeville theater, and eventually to the Movie Palace. The location of Movie Palaces in

downtowns, midtowns and along established transportation routes and in already

established entertainment zones near shopping areas has suggested to some that

shoppers, who were largely female, often combined shopping with a recreational

trip to the movies. Promoters like B.F. Keith cleaned up their shows, revamping

them from their concert saloon formats so that they would appeal to women and

families and increase business. Keith was so successful at this that his

theaters became known as the “Sunday School Circuit”. Thanks to businessman

like him, movies and clean, well appointed theaters in which to show them were

soon viewed as one form of community entertainment that brought the family

together and as especially appealing to women. Contemporary writers who attended early movie

theaters often comment on the presence of women and children and their

perambulators that block the doorways. Women were viewed as arbiters of morality in

this period, extending their moralizing influence out of the home and into

broader community contexts including movies. Because they comprised such a

large percentage of the audience, especially before noon, “women’s” stories of love,

romance and family predominated screenplay subject

matter, especially in the early days of nickelodeons and vaudeville. It has

even been suggested that the opulence of Movie Palaces was largely directed at

the female audience who was thought to prefer it.

Women and men met and mingled at the

movies. Before motion picture theaters, there were few venues where socially

acceptable interaction could occur between unchaperoned

young people. With coming of the movies,

young, unmarried and unchaperoned women as well as

married women could experience a safe night out at the theater alongside men

without the sexual risks associated with less acceptable forms of

entertainment.

Because the relatively cheap

entertainment of the movies and the opulence of the theaters that held them

were available to all classes - rich and poor; native born, immigrant or

non-English speaker (remember the movies were silent at first)

; men, women and children - for the same low price, they were

often referred to as “playhouses for the

masses” , “Democracy’s theater” , “the theater

democratized”, creating the “great audience...non other than the people without

distinction of class.” Moreover, both the vaudeville show and the

later Movie Palace were seen as a venue for the uninitiated and the hopeful

immigrant to learn social etiquette from films, the stage shows, fellow patrons

and from the management who projected slides frequently throughout the program with

instructions for proper comportment such as “Ladies, Please remove your hats”

and “Applause is best shown by clapping the hands”. It has been written that

vaudeville shows, films and the architecture that enclosed them were all part

of a ritual that perpetuated and propagated the American Myth of Success to the

aspiring masses - a celebration of accomplishment to some, and to others a promise that their dreams would

come true. In this regard, this form of popular entertainment can be seen to

have a deeper social significance. It provided the newly urbanized with images,

gestures and vicarious experiences to give their often confusing lives a clear

meaning and their aspirations definition and form.

Even small town Movie Palaces became

symbols of the myth of success and concrete examples of community growth and

importance in small town America. Projects involving the

construction of theaters were often undertaken by a town’s most prominent

businessmen and political figures who often

immortalized themselves in the theater’s name. In small towns theaters were

often more than places of entertainment. They often served the community as

gathering places for civic groups and as centers for service in time of need or

national emergency. Moreover, in many towns the theater was the nicest building

on the square (along with the bank) and the closest most of the population

would ever get to the glamour of Hollywood or the big city theater district.

Describing the development of the

American Movie Palace, Adolf Zukor,

head of Paramount Studios, said, ”..nicks had to go,

theaters replaced shooting galleries, temples replaced theaters, cathedrals

replaced temples.” Movies and

the Movie Palace, the architecture that gave them

form, were purely American phenomena, for which this culture has been praised

and cursed internationally. The Movie Palace was an architectural and cultural

icon equated in the public mind with egalitarianism and democracy in its purest

form, though scholars recognize that it also carried the flaws of racism and

sexism like other institutions of its period.

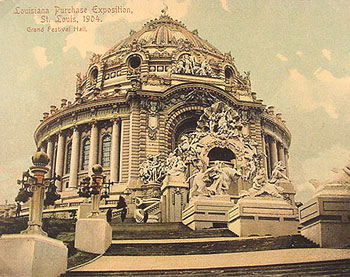

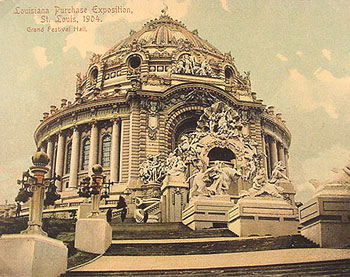

The opulent style of the Movie Palace was both a natural outgrowth of

previous theater architecture shaped by Beaux Arts ideals, most purely

expressed in America by the temporary buildings

constructed for international fairs like the Columbian Exposition (1893) and

the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (1904), but other influences may have been at

work here as well.

The flamboyant

Beaux-Arts style of the Grand Festival Hall

from the St. Louis World’s Fair, 1904

In the

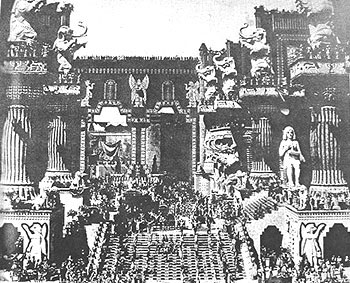

days before the rise of the large American movie studios and flamboyant feature

films like D.W. Griffith’s, Intolerance

(1916), most movies shown in the U.S. were from Europe, primarily from the Gaumont and Pathé Studios of

France. Perhaps the European architecture seen in these films, coupled with the

fantastic architecture drawn from Oriental, Near Eastern and other exotic

sources featured in the set design of movies like Intolerance, contributed to the acceptance and demand for opulent

and exotic Movie Palace architecture of the 1920s.

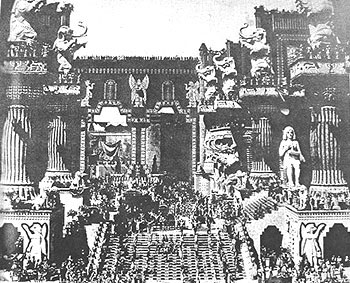

The wild

Near-Eastern inspired set from D.W.

Griffith’s “Intolerance”

(1916)

In addition,

other currents may have contributed. For example, the influence of the only

true Baroque architecture found in the U.S., that seen on the facades and interiors of

Spanish Missions in the Southwest, might

prove to be significant when compared to the facades of Movie Palaces.

The façades if the Mission Dolores, San Francisco (left) and

the San Jose Mission,

San Antonio, Texas

The Coleman Theatre,

Miami Oklahoma (top) and

the Majestic Theatre in East St. Louis, IL. inspired by Spanish

Missions

And

the influence of church interior architecture on that of theatre interiors

should not be overlooked. A striking comparison can be made between theatre

interiors with organ screens flanking the proscenium and church interiors like

that of the Duomo in Todi, Italy.

The altar

end of the Cathedral of Todi in Umbria, Italy

flanked by organ

screens.

The sheer numbers of Movie Palaces that existed in cities and their smaller

cousins that thrived in towns suggest that this type of architecture was

successful in housing motion pictures and appealing to patrons. In addition, it

has been argued that the influence of Movie Palaces may also be seen in

American domestic architecture. It has been suggested that the colonies of

Spanish “haciendas”, half-timbered “Tudor cottages” and “suburban casbahs” built in this period by speculators to satisfy the

public craving for the exotic was first expressed in the tantalizing world of the

local Movie Palace.

The Great Depression ended the building

boom and the period of optimism that gave birth to the Movie Palace idea. Austerity became obligatory

and the advent of sound that required the alteration of theaters difficult to

adapt to the new technology all hobbled the Movie Palace, closing some, altering

others. Many, like the famous Roxy , were eventually torn down, yet a few survive today

and some flourish thanks to efforts of local preservationists and citizens

who still see meaning in George Rapp’s explanation of the real

significance of the opulent Movie

Palace:

“Watch the eyes of a child as it enters the portals of our

great theaters and treads the pathway into fairyland. Watch the bright light in

the eyes of the tired shopgirl who hurries

noiselessly over carpets and sighs with satisfaction as she walks amid

furnishings that once delighted the hearts of queens. See the toil-worn father

whose dreams have never come true, and look inside his heart as he finds strength

and rest within the theater. There you have the answer to why motion picture

theaters are so palatial. Here is a shrine to democracy where there are no

privileged patrons...Do not wonder then at the touches of Italian

Renaissance...or at lobbies and foyers adorned with replicas of precious

masterpieces of another world...and the great sweeping staircases...These are

part of a celestial city-a cavern of many-colored jewels, where iridescent

lights and luxurious fittings heighten the expectation of pleasure. It is

richness unabashed, but richness with a reason...”

Often considered the last great theater

of the Movie Palace Era, Radio City Music Hall in New York City, can be seen as a link between

the opulence of the 1920s and the streamlined Depression Modern or Moderne style of the 1930s.

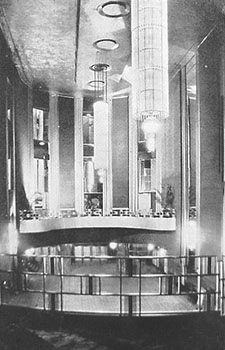

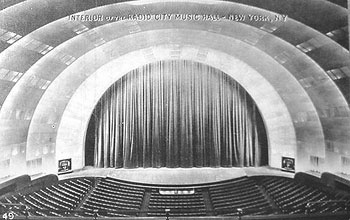

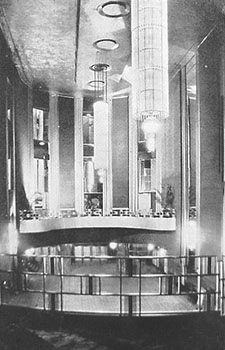

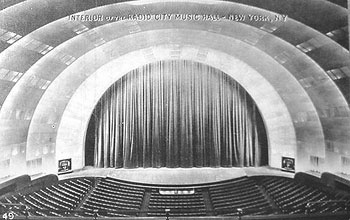

The lobby and

auditorium of Radio City Music Hall

This new

architectural/decorative style was characterized by the reduction of ornament

to simple horizontal lines; simplicity of form embodied in sleek unbroken lines

and clean, broad curves; contrasts in light and shade from structure rather

than applied ornament; honesty of materials like glass block, metals, plastics

and tile used in expressing structure which was reduced to simple geometric

forms and planes. It was the architecture of a smooth-running, modern machine -

in this case a machine for showing movies.

Radio City was born in the Great Depression,

a child of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., the designers of Associated Architects and

hard times which caused the Metropolitan Opera to decline tenancy, and the

young and growing Radio Corporation of America, owner of the National

Broadcasting Company and RKO Pictures, to accept it. Two theaters were to be

included in the complex, and Sam Rothafel (Roxy) was induced to leave his own Roxy

Theater in 1931 to become general director of both. But the interior designs of Donald Desky, one of the founders of the American Union of

Decorative Artists and Craftsmen, made this theater most remarkable.

Desky was born

in upstate New York, and lived in California and then Paris in the turbulent Twenties. There

both Art Deco and the “clean new classicism” of Bauhaus design from Germany influenced him. At

Radio City he and his associates were responsible for all decoration,

furniture, lamps, murals and the enlightened use of a wide array of materials

old and new including Bakelite, fine woods, cork and chrome to create a

“modern” world within the Music Hall and to “impress the customers by sheer

elegance, not by overwhelming them with ornament”, as Desky

himself noted.

The interior design of the Music Hall

was viewed at the time as a triumph of Art Deco. But the simple yet

rich decoration, sharp clean lines and soft textures of the Grand Foyer, and

the lack of ornament, emphasis on curved lines and inventive lighting of the

magnificent, multi-stepped sunburst proscenium arch within the 6200 seat

auditorium all point to something new - to the birth of the Depression Modern

style which was to dominate the decade of the 1930s.

Although Art Deco elements such as radiating arches,

exotic themes and vivid colors of applied decoration often in the form of

terracotta tiles survived the initial days of the Depression, the acceptance of

and need for cheaper-to-build architecture and the popularity of the spare

architecture of the German Depression (Bauhaus and International Style) coupled

with the change in public taste which was promoted by writers and designers of

the time, led to simpler architectural

design in which function, cost and technology, rather than fantasy and

opulence, became the determining factors. In addition, stringent family budgets

often dictated that a walk to a smaller neighborhood theater was a better

choice than spending the money to take a bus downtown to a larger theater.

Maggie Valentine in her book, The Show

Starts at the Sidewalk, describes the typical neighborhood theater of the

1930’s Depression era:

“In plan, neighborhood houses returned to a simple hall

with a box office, sloped floor, screen and projection booth. Because live

entertainment was never a factor, there was no stage (only a narrow apron), no

orchestra pit, and fewer rooms and services. The theatres sat between eight and

twelve hundred people and focused on comfort and efficiency. The lobbies, which

were closer to living rooms than royal parlors, were furnished to create a

homey environment. Small lamps and torchéres had

replaced dripping chandeliers...The screen was smaller and was no longer

“masked” or framed in most houses of this period.”

But since theater owners were as

strapped as anyone else in the Depression, remodeling of a facade or simply the

marquee rather than expensive new construction was often the route followed to

exhibit this new style.

A Moderne marquee added to a Romanesque exterior

The

decade of the 1940s began well for the movie industry and their theaters but

ended with the breakup of the entire system and the economic decline of the

movie industry in the face of new threats of television and drive-in movie theaters.

After American entered World War II, a business boom began - lots of dollars

chasing increasingly scarce goods. Discretionary income was spent on

entertainment, and those movie theaters with good locations thrived. The major

studios saw their rental receipts rise from $193 million dollars in 1939, to

$332 million in 1946, with an attendance of 90 million per week by war’s end.

Theaters often served as centers for war-bond sales and as collection

points for scrap needed for the war effort. Newsreels showing action from the

front were part of the program in the days before TV brought war to our living

rooms. But due to the shortage of labor and materials, and to the 1942 War

Production Board decree ceasing theater construction and commandeering sound and

projection equipment for the military, no new theaters were built in the US between 1942 and 1944, though

some managed remodelings. Yet, thanks in part to the

appointment of John Eberson to the Works Progress

Administration (WPA), President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s officially

recognized movie theaters and movies as important in the maintenance of public

morale and for the presentation of propaganda films to the public. The Motion

Picture Industry was regarded as a necessary war industry - a means to purvey

and propagate the American Way of Life. By 1943 the House Naval

Affairs Subcommittee recommended that $25 million dollars in material and

equipment be set aside for the building of theaters in recognition of the role

of entertainment in supporting public morale while curbing malingering and

moral delinquency. In response, theaters

earned public good will by offering to sell bonds in lieu of selling admissions

on some days.

Before 1943, many theaters were

remodeled, after having their facades and auditoria altered to the spare Moderne style or its stripped down

offshoot, the less decorative Modern Style. During this period innovative ways

to use new and unrestricted materials like concrete, glass, fiberglass, formica and aluminum led to new expressions of modern

design on exteriors, while inside, simpler lines, recessed lighting

emphasizing geometric angles and black-light fluorescent effects provided

lighting and effects even in theaters dimmed for the showing of films.

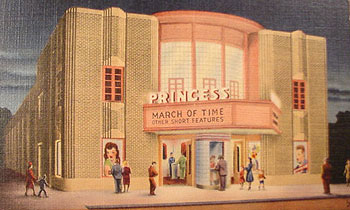

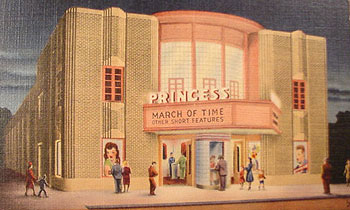

The Princess

Theatre, Aurora, Missouri, a nice

example of the Moderne

style

This “contemporary” theme of movie

theater design continued to be popular into the 1950’s. It served as much an

expression of economic necessity as of style after several body blows to the

movie industry - the Supreme Court anti-trust decision in The United States VS. Paramount et al. in

1948, the post war baby boom, which kept the hordes of young parents, tied to

home, the rise of TV and the increasing popularity of drive-in Theaters. The Supreme Court decision enforced

divorcement of movie exhibition from studio production and distribution,

breaking the stranglehold the “Big 5” (Loews, 20th Century-Fox, Warner’s, Paramount and RKO) held on theaters and the

movies they were permitted to show. In addition, these companies were forced to

divest themselves of the theaters they owned and controlled by splitting

themselves into separate theater and production-distribution companies with no

shared officers held between them.

Initially , independent theaters popped

up after this decision, but the resulting shortage of motion picture product

available to be shown and the consequent rise in admission prices meant that

many soon failed. The process of

divorcement and divestiture was not complete until 1957 by which time film

attendance at all films had fallen by 50% from its high in 1946-47, due largely

to the 90% of American households that had by that date discovered the free

entertainment offered by television.

Many small theaters closed between these years

while the bulk of the public who still attended moves were drawn to the newly

popular drive-in theater to spend their entertainment dollar. They had

discovered that they could bundle baby into the car along with bottles and

diaper bags, paying often by the car load instead of by individual admission.

Younger patrons and their dates realized that they could find a great measure

of privacy in their own car than in the public seats of a traditional movie

theater.

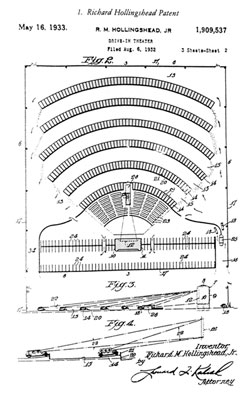

The drive-in theater was first conceived

during the Great Depression. As a young man in the early 1930s, Richard M. Hollingshead, Jr. was searching for a business that could

do well even in hard times. After deciding that food, clothing, automobiles and

movies were the real necessities of life, Hollingshead

opened a deluxe service station where movies were shown outdoors while patrons

waited for service. This idea was

eventually shelved as he experimented with the idea of an outdoor theater for

showing movies. After solving the problems of sight-lines (with terraced rows),

sound delivery (3 large central speakers) and the development of a large 50’

screen he was ready to patent his idea.

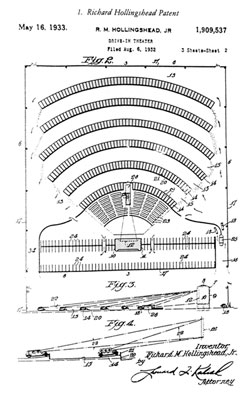

Hollinshead’s Patent for the Drive-In Theatre

The

architectural formula was simple - a ticket booth at the entrance, a small

projection room in the middle of the first row of a fan-shaped series of ramps facing the

screen surrounded by trees and fences accessible over an oiled gravel roadway

to reduce dust and mosquitoes. He opened his theater, called both “Drive-In

Theatre” and “Automobile Movie Theatre”, in Camden, New Jersey on June 6,

1933.

After the first week a concession stand was opened offering beer and cold

snacks.

By the late 1930s the drive-in concept

had spread across the country and many nicknames had been coined for it.

Drive-ins were called ozoners, ramp-houses, rampitoriums, autodeons and

passion pits to name a few. And though,

like indoor theaters, none were built during the war years of the 1940s because

of lack of labor, building materials and the rationing of gasoline and

tires, innovations like in-car speakers,

free window cleaning, playgrounds for children, larger and more varied

concession stands, seating for walk-in patrons, “Rain -A- Way” guards for windshields,

free bottle warming for babies and mobile refreshment carts had been added as

inducements to endure poor sound, dim screens, insects, lack of air

conditioning in the summer and the cold from lack of heating in the winter.

Fostered by the post-war rise in the

availability and use of the automobile, the 1950s brought the golden age of the

drive-in theatre. From 1946 to 1953 almost 3000 were constructed, while only

342 closed. Divorcement and divestiture did not effect

these businesses because they were universally independently owned. At the same

time, only 851 new indoor theatres opened while over 4500 closed their doors.

Out door theatres could accommodate as many as 1300 cars and 1000 walk-in

patrons at the height of their popularity in the early 1950s. Amenities added

during this decade include free insect screens for open car windows

(“Car-Nets”), in-car heaters, live band entertainment with dancing, miniature

golf, free milk and diapers, cafeterias, talent shows, “Beautiful Child”

contests, animal and pet shows, give-aways of all sorts,

treasure hunts, carhops, fashion shows and even laundry service, airplane

parking and marathons with prizes for those who stayed longest.

The public at large loved the drive-in

for its privacy, its casual atmosphere, its amenities and its family oriented

management. But this business was

universally hated by baby-sitters, who were known to picket occasionally

protesting loss of work, and by indoor theatre owners who felt that the decline

of their businesses in the 1950s was due to competition from cheaper drive-ins.

But by the late 1950s even the

drive-ins suffered from the popularity of TV and from the almost country-wide

adoption of daylight savings time which forced the drive-ins, which needed

darkness to show films, to push their showing times later and later in the

summer, their peak earning season. Movie

theatre attendance, indoor and outdoor, reach a new low in 1958 when only 39

million patrons per week went to the movies compared to a high in attendance of

90 million per week in 1946.

Indoor theatre owners and movie

producers retaliated against the rise of unusual amenities offered by drive-ins

and the increased defection to the TV in the living room by developing

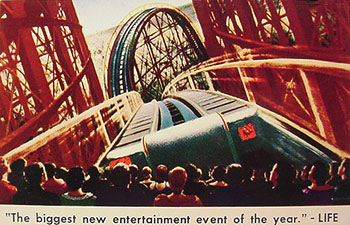

eye-candy not available anywhere but an indoor theatre. Cinerama (3 separate films shown on 3 contiguous curved screens

with 4 projectors {one for sound} to give the illusion of depth and three

dimensions) was first employed in 1952 with the film Cinerama;

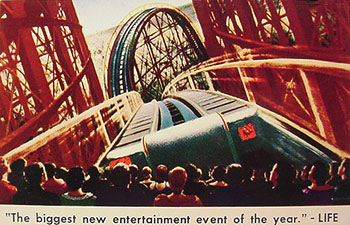

An advertising card

for the St. Louis showing of “Cinerama”

at the Ambassador Theatre

3-D

(a three dimensional effect resulting from shooting the film through 2 parallel

lenses and projecting with two projectors to an audience wearing special

glasses to merge the resulting images) was first seen in the film Bwana Devil in 1952; CinemaScope ( where a special

anamorphic camera lens compressed a wide angle image to the size of regular

movie film which was then projected through another special lens to spread it

out again on the screen) was first seen in 1953 in the movie The Robe; VistaVision (a wide screen

technique employing a larger film image and a greater depth of field and focus)

was inaugurated with White Christmas

in 1954; and Todd A.O. (called

“seamless Cinerama” and invented by Mike Todd and the American Optical Company

to produce the same image as Cinerama with one camera and one projector) was

employed in the film Oklahoma in

1955. Blockbuster “Big” films were

produced that could only be shown in theatres with the new equipment required

for these films. But this equipment was

expensive. By the 1960’s and into the 1970s economics and the reestablishment

of production-distribution-exhibition chains like UA Communications, Inc.,

Cineplex Odeon Corporation and General Cinema Corporation, led to multiple

screen theatres (multiplexes). This brought both an end to the drive-in and the

rise in the threat of the wrecking ball or the remodeler

to surviving Movie Palaces and small neighborhood theaters.

It is largely due to the efforts of the Historic Preservation movement that

grew in strength in the 1970s in response to the American Bicentennial

Celebration in 1976 that the awareness of the importance of our architectural

heritage was rekindled. Along with it came a new appreciation of the Movie Palace, its antecedents and its progeny.

![]()

![]()